Atlanta Fed President: FOMC's Credibility on Inflation Could Be at Stake

Wednesday, December 17th, 2025

Key Points

-

In a new quarterly message, Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic explains his view that, after difficult reflection, he continues to view price stability as the most pressing risk facing the Federal Open Market Committee.

-

Despite cooling labor demand, Bostic writes that it is unclear whether the labor market is significantly out of balance since labor supply growth is slowing because of changes in immigration policy and shifting demographics.

-

Notably, while it's clear labor demand is declining, it is unclear whether cyclical or structural forces are responsible.

-

Bostic acknowledges that some populations—notably Black Americans and recent graduates—are suffering from shifts in the labor market. At the same time, however, the underlying price level has risen by about 20 percent over the past five years, inflicting serious pain, particularly on households of low- and moderate income and wealth.

-

Bostic emphasized that his stance is not immovable. Data releases in the coming weeks could help clarify the state of price stability and employment.

Many of you are probably aware that I will retire as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta when my term ends in February. I will write a farewell message in the first quarter of 2026. In this space, I will focus on the current state of the macroeconomy and my monetary policy stance.

It's safe to say the economy has saved its toughest circumstances for my last days as head of the Atlanta Fed. Risks to both of the Fed's main mandated objectives—price stability and sustainable maximum employment—make this the most challenging policymaking environment since I joined the central bank in 2017.

As this tumultuous year winds down, my Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) colleagues and I face the quandary of softening labor market conditions even as inflation remains materially above the Committee's 2 percent objective. That's a quandary because reducing interest rates to boost employment can heighten risks to price stability. And vice versa: maintaining moderately restrictive monetary policy to battle inflation can dent the labor market. It's a tough spot.

Yet FOMC participants must weigh those delicate tradeoffs in determining appropriate monetary policy. At our last meeting, we did just that. The FOMC decided on another 25 basis-point reduction in the federal funds rate at the December meeting. This action reflects a collective view that risks to the labor market outweigh risks to our price stability mandate. The vote included three dissents, which I view as a clear indication that this was a hard decision and a close call. There are strong arguments on all sides.

As for me, after wrestling with all the considerations, today I continue to view price stability as the clearer and more pressing risk despite shifts in the labor market.

Labor market shifts are difficult to interpret

Let me explain why, starting with the labor market.

The employment market is, at best, moving sideways, and there is good reason to believe that conditions are softening. Employment growth has slowed to around 17,000 net new jobs a month in the six months through November, compared to 139,000 in the prior six months. It's also taking the unemployed longer to find work. These suggest to me that labor demand is cooling.

Despite this, it is unclear to me whether the labor market is significantly out of balance since labor supply growth is also slowing due to changes in immigration policy and shifting demographics. The three-month average for the unemployment rate for August, September, and November—the government did not release unemployment for October—was 4.4 percent, compared to 4.2 percent in the same months a year earlier.

And careful analysis by economists on our staff suggests that the labor market is likely not at a negative inflection point. Big picture, I do not view a severe labor market downturn as the most likely near-term outcome.

All this said, there are reasons why it is difficult to divine a clear signal to guide policy from prevailing labor market indicators. For starters, while labor demand is clearly declining, it is unclear whether cyclical or structural forces are responsible.

As I see it, there are at least four primary drivers of declining labor demand. One, a number of firms report that they are normalizing staffing from high headcounts amassed in response to elevated demand for goods and services during much of the pandemic period. Two, many business leaders are optimistic that they can use technology to replace jobs that firms would normally need to hire for. Respondents to our surveys report plans to significantly increase investment in technologies like artificial intelligence in 2026.

Third, firms have been hesitant to hire amid uncertainty triggered by manifold policy changes this year. Finally, numerous firms are wrestling with dwindling margins squeezed by higher costs and lower consumer demand. As a result, executives at these companies are laser-focused on headcounts.

I would categorize the first two of those reasons—normalizing staff sizes and labor-replacing technology—as structural in nature, and thus outside of the purview of monetary policy. Regarding the third driver, I realize there is mixed evidence and opinion on uncertainty shocks. But my strong sense is that volatility in fiscal, trade, and other policies is not something that any modest degree of monetary stimulus can overcome. In other words, I view uncertainty as a structural impediment in the current environment.

The signal to take from the last element—shrinking margins—is also not completely clear, since some of the margin squeeze may be due to cyclical factors. But my contacts have consistently reported that much of the margin pressure that firms are facing is specifically due to the high inflation of the past five years, which has raised input costs and reduced consumer demand from low- and middle-income households.

Further, if we were experiencing broad-based cyclical labor market weakness, I would expect to see signs of significant economic weakening. I see some indications of gradual softening, yes. But the most recent estimates from our GDPNow "nowcast" model are holding north of 3 percent for the July–September quarter, far above the pre- and post-pandemic average. That pace of economic growth will probably slow in the quarters to come. Our staff forecast and the consensus among professional forecasters for 2026 is around 2 percent. That outlook and feedback from business contacts point to moderation rather than the sort of pronounced slowdown that could cause a labor market collapse.

There are also sectoral questions in employment markets, as different economic sectors face different labor challenges—shortages of skilled workers in some fields, and shortages of available jobs in others. And labor demand isn't the only issue. The supply of workers is hardly growing due to an aging population and changes in immigration policy.

All this tells me we still need to decipher a morass of dynamics to determine the labor market's status relative to the FOMC's goal of sustainable maximum employment. Before we prescribe strong remedies for today's labor market conditions—whether remedies come from monetary policy or elsewhere—we should understand the root causes of the shifts, and not just the symptoms. After all, strong remedies can produce unwanted side effects.

If we are in fact entering a cyclical labor market downturn, then a monetary policy response is probably in order. Some of my FOMC colleagues obviously think that is the case, as evidenced by reductions in the federal funds rate at the past three meetings. By contrast, if labor market shifts reflect more structural forces such as demographics, reduced immigration, technological advances, or other fundamental changes in economic relationships, then monetary policy is likely not the ideal first-level response.

Credibility and price stability

Now, turning to price stability, it is helpful to remember that inflation has exceeded the 2 percent target for nearly five years. During this time, the price level has increased by approximately 20 percent, with prices for necessities like food, shelter, and insurance rising by even more. The September reading on the all-important personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, the latest we have, lingered well above the goal—at 2.8 percent.

So far, new tariffs have not fueled a pronounced spike in inflation, yet import duties have buoyed goods prices since the spring. Combined with elevated inflation for "supercore" services—those excluding housing—faster rising goods prices are keeping headline PCE inflation near 3 percent.

And based on the data in hand and numerous forward-looking indicators, I see little to suggest that price pressures will dissipate before mid to late 2026, at the earliest, and expect inflation to remain above 2.5 percent even at the end of 2026.

In coming to this view, I'm leaning on information from our Economic Survey Research Center. Evidence from our three major surveys points decisively in one direction—continued upward pressure on costs and prices. Firms in our surveys expect to raise prices well into 2026, and by substantially more than 2 percent. Especially worrisome is the fact that these inflationary expectations are not limited to importers directly affected by tariffs.

I trust our survey findings for a couple of reasons in particular. First, the survey data are especially useful when traditional aggregate statistics are absent, slow in coming, or incomplete, like after the recent government shutdown. Second, our survey results have proven to be reliable gauges and predictors of economic activity, as good as the best forecasts.

That gets me to the real rub: If underlying inflationary forces linger for many months to come, I am concerned that the public and price setters will eventually doubt that the FOMC will hit the inflation target in any reasonable time frame. Will the public lose faith after five years of above-target inflation? Six years?

Nobody knows. But what we do know is that credibility is a cornerstone of effective monetary policy. I am mindful of just how precious and hard-won our credibility is, and how difficult it would be to regain that credibility should it slip away. In my view, a half decade—and likely soon to be longer—of missing the inflation target could well imperil the Committee's credibility as a steward of price stability.

Serious trouble awaits if inflation expectations for the medium- and longer-term drift upward and influence behavior in ways that produce higher long-run realized inflation. Should those things happen, history suggests that pain in the form of higher unemployment could be required to pull inflation expectations back into the long-run target range.

To be clear, I'm not suggesting that conditions today mirror the Great Inflation of the 1970s and '80s. Still, it's worth remembering that erratic monetary policy in that period helped to sustain 10-plus years of elevated inflation that was finally subdued only after a double-dip recession and the nation's highest unemployment rate since World War II, excluding the recent pandemic period.

My position isn't immovable

I appreciate the concerns of colleagues who view labor market vulnerability as a more urgent danger than inflation. And I acknowledge real suffering in some populations. Unemployment among Black Americans and recent college graduates has climbed sharply, and the average spell of unemployment is longer than it was a year ago.

But it's also the case that households, especially those with low and moderate levels of income and wealth, are feeling tangible pain from inflation, a pain they have been bearing for years now. I think it is at least as important to acknowledge and respond to this as it is to respond to the risk of prospective future labor market weakness.

Whatever the underlying causes of labor market shifts, there's no question the objectives of price stability and sustainable maximum employment are both under pressure. Straw polls at my meetings with contacts and staff reflect a broader shift in sentiment: votes that a year ago were 14-1 toward inflation as the bigger risk are now very close. In some rooms, labor market concerns carry the day. As I said at the outset, this is a close call.

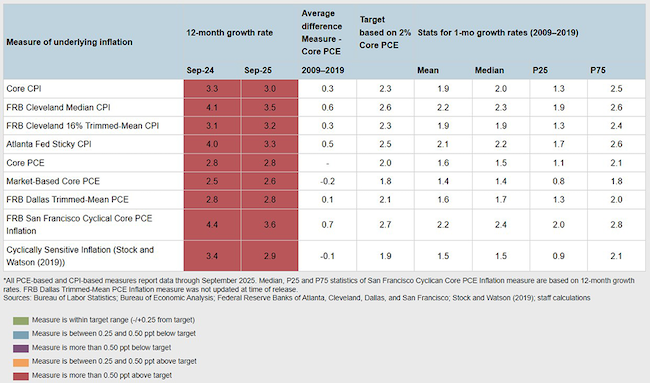

In my final analysis, as I write in mid-December, signals from the labor market remain too ambiguous to warrant an aggressive monetary policy response when weighed against the more definitive risks of ongoing inflationary pressures. I think our Underlying Inflation Dashboard illustrates the case nicely. The dashboard shows numerous measures of fundamental price pressures. Red means too high, and the table is bathed in red.

High prices and inflation are driving so much of what we wrestle with today, and it is essential that we manage that price stability risk.

Let me be clear: I am in no way dismissing concerns about the health of the labor market. I'm just not convinced right now that aggressive monetary policy is the proper remedy. In the current circumstances, moving monetary policy near or into accommodative territory, which further federal funds rate cuts will do, risks exacerbating already elevated inflation and untethering the inflation expectations of businesses and consumers. That is not a risk I would choose to take right now.

One last thing: I'm not immovable on this. New information could lead me to reach a different understanding of the risks to our employment and inflation mandates. Importantly, we will be getting a lot of data in the next few weeks, as the federal agencies release statistics for the months when the government was shut down. These data could provide key insights that reveal how our measures have evolved and shed light on whether weakness in labor markets and persistence of inflation have changed in material ways. I look forward to getting those data and additional intelligence from the many other sources we rely upon.

This is a particularly difficult environment for monetary policymakers. But this is what we signed up for: to pursue stable prices and maximum employment as the foundation for an economy that works for all Americans. That is what I have endeavored to do for these past eight years, and it is what my FOMC colleagues and I will continue to do.